25 years of springer*in

/5

A look back. A bright green chameleon stands at beginning. Motionless, somewhat like an indecisive tightrope-walker. Its eyes visibly shut. This work by Florian Pumhösl, realized together with Andreas Pawlik and Matthias Hermann, decorates the cover of the first issue of springerin, the name of which is two letters shorter at this point, still in its masculine form: springer. Florian Pumhösl thus metaphorically anticipates the path forward, which is destined to repeatedly cross that of the Kontakt Collection later on.

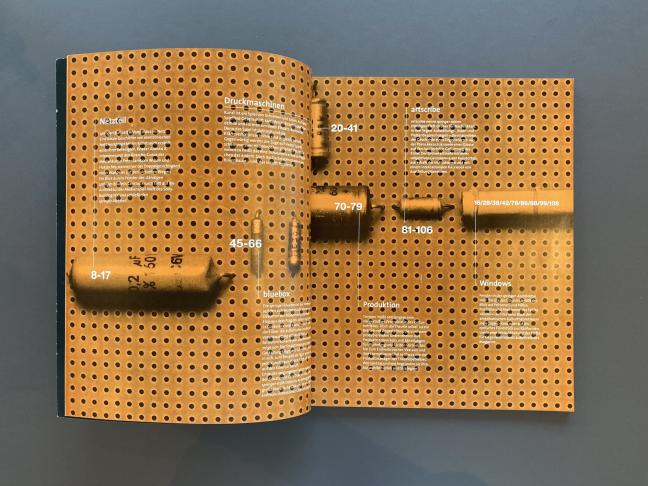

25 years ago: the history of springerin began back in the mid-1990s. The Internet was still in its nascence—with search engines not yet monopolized, their algorithms not yet programmed. In this atmosphere of change, the magazine’s first issue already featured a section entitled “Netzteil,” which covered early topics raised by the process of digitization that was gradually setting in. Similar things happened on the springer website in what was something of a proto-blog authored by an international pool of correspondents. The still rather young cultural studies discipline, represented by theoreticians such as Lawrence Grossberg and Stuart Hall, likewise found a place in the magazine quite early on. The budding globalization discourses of the 2000s, the discourse on postcolonialism associated with Documenta 11 in 2002 (curated by Okwui Enwezor), and the dominant thought-construct of “the West and the rest of the world” all gave rise to themed issues with concrete focuses on other regions outside the established canon. And a further central concern was the furtherance of the political as an aspect of art criticism.

At this point in time, the Austrian arts scene was still very much under the influence of Viennese Actionism, which lay not that far in the past. Perspectives were frozen, with most eyes cast toward Germany and America. In this atmosphere, springerin was a rare example of attention directed in the opposite direction—towards Eastern Europe. The prevailing term Ostkunst [Eastern Art] had for far too long been covered in a layer of dust. A seemingly immovable wall seemed to run all along the invisible border between the monumental categories of “West” and “East”, with these geographic designations still implicitly present in our thoughts and discourses even after the fall of the Iron Curtain. Against this backdrop, springerin was concerned from the very beginning with the both concrete and discursive dissolution of regional labels, advocating a global historiography of art and a departure from the construct of “Central Europe.”

A pivotal moment in these efforts was an exhibition and symposium organized by springerin in 1999 and entitled “translocation_(new) media/art.” There, one experienced works by a selection of works by artists who were still barely known in “Europe”—artists including Sanja Iveković, Milica Tomić, Luchezar Boyadjiev, and many others. “translocation_(new) media/art” was an early attempt to shine a light on the former “East”, ex-Yugoslavia, and the media art that was underrepresented there. This commonality with springerin that the Kontakt Collection shared ever since its founding prominently manifested itself once again in the 2016 springerin issue “Parallax Views”, the content of which was developed in cooperation with Kontakt.

Many hundreds of themes later, back in the present: some discourses have vanished only to return in other words. Discourses mark moments, and one moment follows the other and vanishes once more. The gaze back into the future.

Ada Karlbauer

Ada Karlbauer is a writer. She lives and works in Vienna.

September 2020

25 years ago: the history of springerin began back in the mid-1990s. The Internet was still in its nascence—with search engines not yet monopolized, their algorithms not yet programmed. In this atmosphere of change, the magazine’s first issue already featured a section entitled “Netzteil,” which covered early topics raised by the process of digitization that was gradually setting in. Similar things happened on the springer website in what was something of a proto-blog authored by an international pool of correspondents. The still rather young cultural studies discipline, represented by theoreticians such as Lawrence Grossberg and Stuart Hall, likewise found a place in the magazine quite early on. The budding globalization discourses of the 2000s, the discourse on postcolonialism associated with Documenta 11 in 2002 (curated by Okwui Enwezor), and the dominant thought-construct of “the West and the rest of the world” all gave rise to themed issues with concrete focuses on other regions outside the established canon. And a further central concern was the furtherance of the political as an aspect of art criticism.

At this point in time, the Austrian arts scene was still very much under the influence of Viennese Actionism, which lay not that far in the past. Perspectives were frozen, with most eyes cast toward Germany and America. In this atmosphere, springerin was a rare example of attention directed in the opposite direction—towards Eastern Europe. The prevailing term Ostkunst [Eastern Art] had for far too long been covered in a layer of dust. A seemingly immovable wall seemed to run all along the invisible border between the monumental categories of “West” and “East”, with these geographic designations still implicitly present in our thoughts and discourses even after the fall of the Iron Curtain. Against this backdrop, springerin was concerned from the very beginning with the both concrete and discursive dissolution of regional labels, advocating a global historiography of art and a departure from the construct of “Central Europe.”

A pivotal moment in these efforts was an exhibition and symposium organized by springerin in 1999 and entitled “translocation_(new) media/art.” There, one experienced works by a selection of works by artists who were still barely known in “Europe”—artists including Sanja Iveković, Milica Tomić, Luchezar Boyadjiev, and many others. “translocation_(new) media/art” was an early attempt to shine a light on the former “East”, ex-Yugoslavia, and the media art that was underrepresented there. This commonality with springerin that the Kontakt Collection shared ever since its founding prominently manifested itself once again in the 2016 springerin issue “Parallax Views”, the content of which was developed in cooperation with Kontakt.

Many hundreds of themes later, back in the present: some discourses have vanished only to return in other words. Discourses mark moments, and one moment follows the other and vanishes once more. The gaze back into the future.

Ada Karlbauer

Ada Karlbauer is a writer. She lives and works in Vienna.

September 2020