Artfan Revisited

/6

“Artfan was the form that corresponded to the substance addressed therein”,1 it was once said by the publishers of this Viennese fanzine (1991–1996). Ariane Müller and Linda Bilda, previously active in the Austrian section of the Situationist International (SI), were the anonymous duo behind what was a hand-copied zine that, back then, they smuggled into the scene more or less on their own. And that they soon linked up with a multitude of network nodes, spread out far beyond the confines of Vienna and Austria and still acting in a scattered and isolated fashion, to form a critical project alliance. “Context” [Zusammenhang] was the explicitly trivial code word for the loose network that arose between Cologne, Berlin, Stuttgart, Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Zurich, and also Vienna starting in the 1990s. It was a network devoted primarily to the impulses emanating above all from New York at that time, impulses entailing criticism of institutions, economics, and representation.

Taking up what was “exciting, new” about such impulses, arriving at a “new language” for it all while also “allowing and giving the artists their own voice,” as Ariane Müller ascertained later on, was of programmatic significance to this fanzine based in an office on Engerthstraße. It was an undertaking that advanced into a veritable journalistic vacuum—for outside everyday journalism, which was itself quite thin on the ground in Austria back then, there was hardly any noteworthy reporting being done with regard to current developments in art. It was thus all the more urgent, including in terms of the overall tone of discourse, that such a project—a project that is still well worth reading today for its directness and its highly pointed flippancy—be brought forth. Brought forth in order to produce an according measure of confrontation, ripping the art that it addressed out of the indifferently objective perspective from which it was viewed, as it were, while at the same time impressively confirming the value of that which was only spoken, that which was quite often expressed informally but hardly ever appeared in serious art criticism.

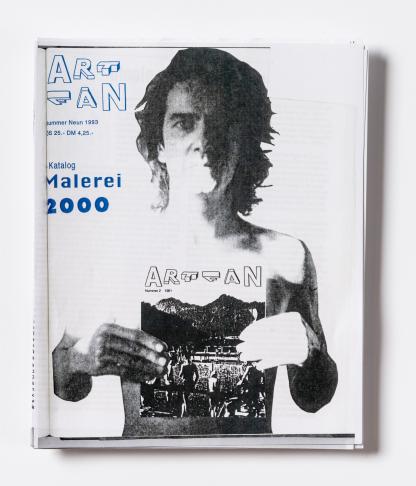

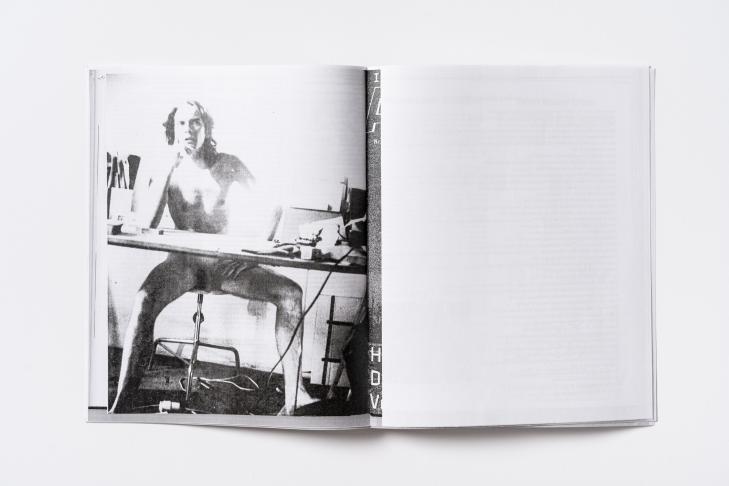

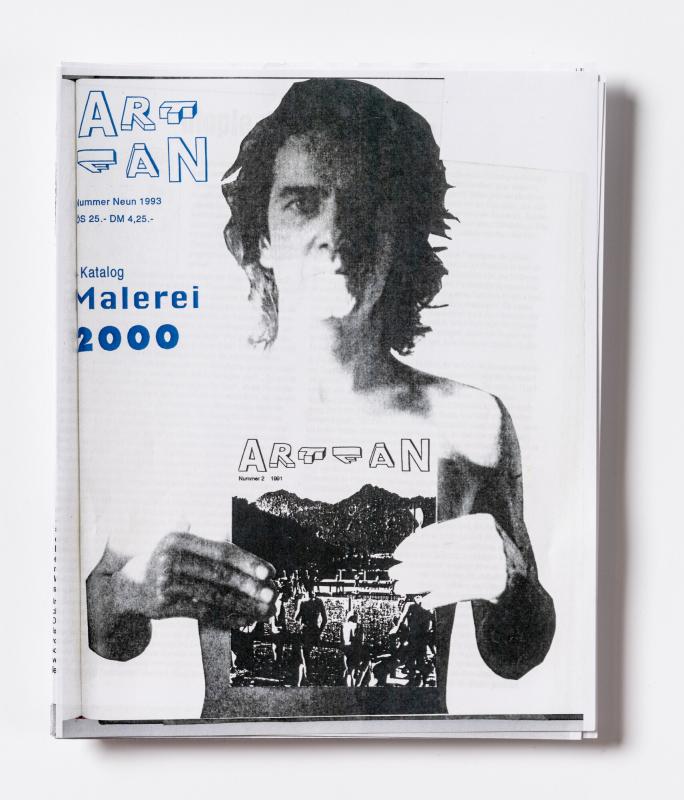

A total of 13 issues appeared beginning in January 1991 (most of them in ’91 and ’92). Although 13 isn’t exactly correct, since—at least in terms of numbering—the second issue was leapfrogged. (In what was very much an inside joke, the artist Marcus Geiger held “Artfan No. 2”, which never actually existed, into the camera on the cover of No. 9 / 1993). Such tongue-in-cheek excursions—détournements, if one will—abounded in the publishers’ situationist-flavored doings … such as on the cover of No. 1, which featured a photograph by Friedl Kubelka from 1970 showing the Trio Kurt Kalb, Hans Neuffer (with African tribal mask), and Christian Ludwig Attersee, all of whom effectively had little to do with Artfan’s notion of art; or when in response to the Los Angeles Riots of 1992, a historical commentary on the 1965 Watts Riots by the Situationist International was appropriated and applied to the present (with the original text being adapted by the Freie Klasse [Open Class] Vienna).

On the whole, a fan-like approach characterized by edginess and insouciance (including in a confrontative sense) prevailed, whether in the often quite blunt brief reviews discussions—some of them with hand-drawn illustrations—or in the occasionally quite long conversations with artists that sometimes even required special supplements (see, for example, the almost book-length interview with Martin Kippenberger in No. 5 / 1991) in order to account for all that had been said. (A few examples and/or excerpts from the interviews conducted by Ariane Müller can be found here https://arianemueller.org/artfan/ ) Amidst all this, Müller’s and Bilda’s interviewing never shied away from expressing enthusiasm for this or that, just like they also never shied away from throwing the perceived defects of the interviewees’ works in their faces.

The fact that they devoted considerable space in their issues to themes such as feminism and urbanism (strands of discourse that had previously received precious little attention in the Austrian art world) cannot be appreciated enough today. And a special edition, the zine’s penultimate issue (12/1995) produced by the two in response to an invitation by the Salzburger Kunstverein on the occasion of an exhibition there by its then-head Silvia Eiblmayr, represents an eminent historiographic testimonial: therein, the numerous minor instances of friction and disagreement that characterize such cooperative efforts were taken up as an explicit driver of the issue’s analysis rather than being graciously swept under the rug.

In 1995, Bilda and Müller traveled together with the situationism authority Roberto Ohrt (author of Phantom Avantgarde) to the Yugoslav successor-states in order to research the war that was still raging there at that time for a special issue. Although this project had been denied ministerial funding based on the argument that the war in Yugoslavia was “not a topic for fine art”, it still resulted in a highly appealing and pointed—albeit reduced—commentary. The lion’s share of this issue consists of a photo story revolving around a Big Jim action figure (the male counterpart to Barbie) that recounts an oedipal ménage-à-trois—which might actually be better described as “anti-oedipal”, since the speech bubbles contain texts appropriated from sources such as Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus. The fact that its way of addressing the war could only ever be indirect and never free from distortion was also underlined by a historical eyewitness account by Hans Landauer, one of the last Austrians still alive at the time who had fought in the Spanish Civil War. Such critical counterpoints to contemporary events can also be found in a further pictorial story in which color photographs of baked goods and dumplings are used to address the contradiction between socialist utopia and capitalist reality.

1996 saw the publication of a final, comparatively opulent edition. The highly divergent “issues” addressed therein: urbanism, monument debates, criticism of technology, and so on. There was only one conversation with an artist (Fatih Aydoğdu). And perhaps it was indeed the case that the publication’s original program already had, by that time, been fulfilled in a certain sense. Perhaps the “new” and “exciting” could only be lent “a voice” for so long before itself beginning to be overgrown by other rhizomatic developments and ramifications. Before giving way to a diversification or a multiplicity of perspectives to which the pages of a traditional fanzine could do only partial justice. Prior to that, however, Artfan had set an example that was in equal measures urgent and timely. An example to which, even at a distance of 30 years, one can still return for refreshing realizations.

[1] Linda Bilda / Ariane Müller, “Artfan,” in: Marius Babias (ed.), Im Zentrum der Peripherie. Kunstvermittlung und Vermittlungskunst in den 90er Jahren. Dresden/Basel 1995, p. 324.

Christian Höller is co-editor of “springerin - Hefte für Gegenwartskunst;” recently, he co-edited “White Space in White Space / Biely priestor v bielom priestore, 1973−1982. Stano Filko, Miloš Laky and Ján Zavarský,” together with Daniel Grúň and Kathrin Rhomberg (Schlebrügge.Editor 2021).

May 2022

Taking up what was “exciting, new” about such impulses, arriving at a “new language” for it all while also “allowing and giving the artists their own voice,” as Ariane Müller ascertained later on, was of programmatic significance to this fanzine based in an office on Engerthstraße. It was an undertaking that advanced into a veritable journalistic vacuum—for outside everyday journalism, which was itself quite thin on the ground in Austria back then, there was hardly any noteworthy reporting being done with regard to current developments in art. It was thus all the more urgent, including in terms of the overall tone of discourse, that such a project—a project that is still well worth reading today for its directness and its highly pointed flippancy—be brought forth. Brought forth in order to produce an according measure of confrontation, ripping the art that it addressed out of the indifferently objective perspective from which it was viewed, as it were, while at the same time impressively confirming the value of that which was only spoken, that which was quite often expressed informally but hardly ever appeared in serious art criticism.

A total of 13 issues appeared beginning in January 1991 (most of them in ’91 and ’92). Although 13 isn’t exactly correct, since—at least in terms of numbering—the second issue was leapfrogged. (In what was very much an inside joke, the artist Marcus Geiger held “Artfan No. 2”, which never actually existed, into the camera on the cover of No. 9 / 1993). Such tongue-in-cheek excursions—détournements, if one will—abounded in the publishers’ situationist-flavored doings … such as on the cover of No. 1, which featured a photograph by Friedl Kubelka from 1970 showing the Trio Kurt Kalb, Hans Neuffer (with African tribal mask), and Christian Ludwig Attersee, all of whom effectively had little to do with Artfan’s notion of art; or when in response to the Los Angeles Riots of 1992, a historical commentary on the 1965 Watts Riots by the Situationist International was appropriated and applied to the present (with the original text being adapted by the Freie Klasse [Open Class] Vienna).

On the whole, a fan-like approach characterized by edginess and insouciance (including in a confrontative sense) prevailed, whether in the often quite blunt brief reviews discussions—some of them with hand-drawn illustrations—or in the occasionally quite long conversations with artists that sometimes even required special supplements (see, for example, the almost book-length interview with Martin Kippenberger in No. 5 / 1991) in order to account for all that had been said. (A few examples and/or excerpts from the interviews conducted by Ariane Müller can be found here https://arianemueller.org/artfan/ ) Amidst all this, Müller’s and Bilda’s interviewing never shied away from expressing enthusiasm for this or that, just like they also never shied away from throwing the perceived defects of the interviewees’ works in their faces.

The fact that they devoted considerable space in their issues to themes such as feminism and urbanism (strands of discourse that had previously received precious little attention in the Austrian art world) cannot be appreciated enough today. And a special edition, the zine’s penultimate issue (12/1995) produced by the two in response to an invitation by the Salzburger Kunstverein on the occasion of an exhibition there by its then-head Silvia Eiblmayr, represents an eminent historiographic testimonial: therein, the numerous minor instances of friction and disagreement that characterize such cooperative efforts were taken up as an explicit driver of the issue’s analysis rather than being graciously swept under the rug.

In 1995, Bilda and Müller traveled together with the situationism authority Roberto Ohrt (author of Phantom Avantgarde) to the Yugoslav successor-states in order to research the war that was still raging there at that time for a special issue. Although this project had been denied ministerial funding based on the argument that the war in Yugoslavia was “not a topic for fine art”, it still resulted in a highly appealing and pointed—albeit reduced—commentary. The lion’s share of this issue consists of a photo story revolving around a Big Jim action figure (the male counterpart to Barbie) that recounts an oedipal ménage-à-trois—which might actually be better described as “anti-oedipal”, since the speech bubbles contain texts appropriated from sources such as Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus. The fact that its way of addressing the war could only ever be indirect and never free from distortion was also underlined by a historical eyewitness account by Hans Landauer, one of the last Austrians still alive at the time who had fought in the Spanish Civil War. Such critical counterpoints to contemporary events can also be found in a further pictorial story in which color photographs of baked goods and dumplings are used to address the contradiction between socialist utopia and capitalist reality.

1996 saw the publication of a final, comparatively opulent edition. The highly divergent “issues” addressed therein: urbanism, monument debates, criticism of technology, and so on. There was only one conversation with an artist (Fatih Aydoğdu). And perhaps it was indeed the case that the publication’s original program already had, by that time, been fulfilled in a certain sense. Perhaps the “new” and “exciting” could only be lent “a voice” for so long before itself beginning to be overgrown by other rhizomatic developments and ramifications. Before giving way to a diversification or a multiplicity of perspectives to which the pages of a traditional fanzine could do only partial justice. Prior to that, however, Artfan had set an example that was in equal measures urgent and timely. An example to which, even at a distance of 30 years, one can still return for refreshing realizations.

[1] Linda Bilda / Ariane Müller, “Artfan,” in: Marius Babias (ed.), Im Zentrum der Peripherie. Kunstvermittlung und Vermittlungskunst in den 90er Jahren. Dresden/Basel 1995, p. 324.

Christian Höller is co-editor of “springerin - Hefte für Gegenwartskunst;” recently, he co-edited “White Space in White Space / Biely priestor v bielom priestore, 1973−1982. Stano Filko, Miloš Laky and Ján Zavarský,” together with Daniel Grúň and Kathrin Rhomberg (Schlebrügge.Editor 2021).

May 2022