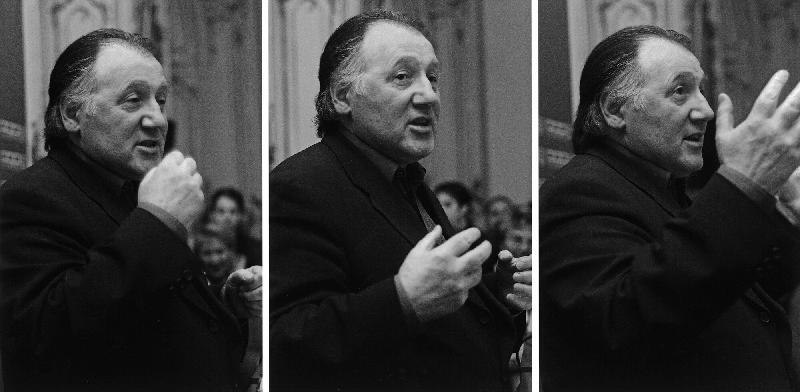

Peter Weibel1944–2023

/1

“Life is a short-term disguise for death,” Peter Weibel firmly believed. Even so, he did harbor fundamental doubts about the conditio humana and attempted to escape it his entire life long. He ultimately failed in this, departing from our world in Karlsruhe on 1 March. And it is to be feared that his assessment mentioned above was indeed correct, seeing as one is dead for far longer than one could ever be alive.

Human beings, he said, exist in a “prison of space and time.” So what else to do but work to effect free spaces, expansions, and circumlocutions, to tax the body to the fullest in order to simultaneously liberate oneself from it as in Viennese Actionism? Subsequently fusing it with the apparatus, enabling observation of one’s own observations so as to demolish existing natural laws, conceiving of any new natural laws’ discovery as an expansion, was Weibel’s central project—with the acceleration of this process being his declared goal. To a navigator of the “pluriverse”, the data-based postindustrial dynamics of information, new experiences in space and time are necessary and achievable. The multiple worlds between which Weibel alternated back and forth explain his striving for omnipresence and simultaneity. Hardly to be grasped and not to be limited, he would surely have desired to vacate his corporeal confines and see his spirit liberated. Doing so would have allowed him to neutralize the very dilemma that he considered one of the most central of all: that of how every decision suppresses countless other possibilities. In a purely superficial sense, this was clear to see in the large-scale exhibitions that he curated, with their unusually long lists of featured artists. But that which uninformed and ignorant circles frequently criticized as exorbitance and randomness was in fact the clear vision of a universalist who refused to accept either-or and would in no case allow himself to be limited. The historian William M. Johnston referred to Weibel as an “unclassifiable.” It seemed plausible to him that this “polyartist”—who, as a versatile phenomenologist born in Odessa in 1944, studied and internalized the various avant-garde movements—was forever attempting to cover multiple disciplines. Weibel himself, held Johnston, embodied the sort of multidisciplinarity that studying the culture of the Habsburg dual monarchy indeed necessitates. The multiethnic mixture of “Kakania” constituted both Weibel’s cultural basis and his source of friction. In one of his final interviews, Peter Weibel identified the most significant factors underlying human coexistence as being inclusion and exclusion—words that featured in the title of a 1996 exhibition that he curated in Graz. That exhibition was, in fact, also associated with the attempt to establish a new cartography of art in the era of postcolonialism and global migration. Art, in its conception as an invention of the West, was considered by Weibel to embody abundantly clear evidence of massive exclusion. Weibel accepted no borders, neither in the global context nor in immediate proximity to the Balkan countries: “Art’s mission consists in opening doors where nobody sees them.” This was a conviction that he applied both personally and in his general thought.

In the 1997 exhibition “U3: The 2nd Triennial of Contemporary Slovene Art” in Ljubljana, which he curated, Weibel once again defined art beyond the “white cube” as media spaces, social spaces, and spaces beyond geopolitics. And in the 2002 exhibition “In Search of Balkania” in Graz, he predicted—with terrifying accuracy, as one can now see—the marginalization of the West. It is precisely this prescience that now concerns us in a very lasting way. Weibel was among the signatories of the “Manifesto for Peace.” Regarding the war in Ukraine, he called urgently for the advancement of peace negotiations rather than for renewed armaments shipments as a matter of course—embodying the “unclassifiable” as an unpleasantly nonconforming figure who puts his finger directly on the wound.

The ZKM in Karlsruhe, an institution that would seem to be visiting us from the future, was to be his final and most monumental artwork. This research center is fundamentally committed to inclusion, and its liaison between theorization and artistic practice gave rise to an open field of action where Weibel could alternate between his various identities. So was he a theorist, an artist, a researcher, a curator? Why decide? He never fit any existing boxes, and precisely that was so liberating for those around him whom he repeatedly helped back onto their feet with his theories and artworks. His own works do not adhere to any market logic, instead materializing complex concepts that reach far beyond art. In this, the tradition of formal thought, of criticizing language and reality—a tradition nearly forgotten in this country—may have been a contributing factor.

Peter Weibel always viewed the aspirations of the Enlightenment as central to his own intellectual doings as a libertarian spirit who consistently accorded pride of place to knowledge and responsibility. It would follow that criticism and subversion embody prerequisites for the ability to think about freedom at all. His physical presence will most certainly be missed—but his intellectual heritage will, happily, allow us to remain in communion with him.

Günther Holler-Schuster

Günther Holler-Schuster is an art historian, writer, curator, and artist. He works as curator and head of the collection at Neue Galerie Graz, where Peter Weibel served as chief curator from 1992 to 2011. Together with Martin Behr, Holler-Schuster has been part of the artist duo G.R.A.M. since 1987.

March 2023

Human beings, he said, exist in a “prison of space and time.” So what else to do but work to effect free spaces, expansions, and circumlocutions, to tax the body to the fullest in order to simultaneously liberate oneself from it as in Viennese Actionism? Subsequently fusing it with the apparatus, enabling observation of one’s own observations so as to demolish existing natural laws, conceiving of any new natural laws’ discovery as an expansion, was Weibel’s central project—with the acceleration of this process being his declared goal. To a navigator of the “pluriverse”, the data-based postindustrial dynamics of information, new experiences in space and time are necessary and achievable. The multiple worlds between which Weibel alternated back and forth explain his striving for omnipresence and simultaneity. Hardly to be grasped and not to be limited, he would surely have desired to vacate his corporeal confines and see his spirit liberated. Doing so would have allowed him to neutralize the very dilemma that he considered one of the most central of all: that of how every decision suppresses countless other possibilities. In a purely superficial sense, this was clear to see in the large-scale exhibitions that he curated, with their unusually long lists of featured artists. But that which uninformed and ignorant circles frequently criticized as exorbitance and randomness was in fact the clear vision of a universalist who refused to accept either-or and would in no case allow himself to be limited. The historian William M. Johnston referred to Weibel as an “unclassifiable.” It seemed plausible to him that this “polyartist”—who, as a versatile phenomenologist born in Odessa in 1944, studied and internalized the various avant-garde movements—was forever attempting to cover multiple disciplines. Weibel himself, held Johnston, embodied the sort of multidisciplinarity that studying the culture of the Habsburg dual monarchy indeed necessitates. The multiethnic mixture of “Kakania” constituted both Weibel’s cultural basis and his source of friction. In one of his final interviews, Peter Weibel identified the most significant factors underlying human coexistence as being inclusion and exclusion—words that featured in the title of a 1996 exhibition that he curated in Graz. That exhibition was, in fact, also associated with the attempt to establish a new cartography of art in the era of postcolonialism and global migration. Art, in its conception as an invention of the West, was considered by Weibel to embody abundantly clear evidence of massive exclusion. Weibel accepted no borders, neither in the global context nor in immediate proximity to the Balkan countries: “Art’s mission consists in opening doors where nobody sees them.” This was a conviction that he applied both personally and in his general thought.

In the 1997 exhibition “U3: The 2nd Triennial of Contemporary Slovene Art” in Ljubljana, which he curated, Weibel once again defined art beyond the “white cube” as media spaces, social spaces, and spaces beyond geopolitics. And in the 2002 exhibition “In Search of Balkania” in Graz, he predicted—with terrifying accuracy, as one can now see—the marginalization of the West. It is precisely this prescience that now concerns us in a very lasting way. Weibel was among the signatories of the “Manifesto for Peace.” Regarding the war in Ukraine, he called urgently for the advancement of peace negotiations rather than for renewed armaments shipments as a matter of course—embodying the “unclassifiable” as an unpleasantly nonconforming figure who puts his finger directly on the wound.

The ZKM in Karlsruhe, an institution that would seem to be visiting us from the future, was to be his final and most monumental artwork. This research center is fundamentally committed to inclusion, and its liaison between theorization and artistic practice gave rise to an open field of action where Weibel could alternate between his various identities. So was he a theorist, an artist, a researcher, a curator? Why decide? He never fit any existing boxes, and precisely that was so liberating for those around him whom he repeatedly helped back onto their feet with his theories and artworks. His own works do not adhere to any market logic, instead materializing complex concepts that reach far beyond art. In this, the tradition of formal thought, of criticizing language and reality—a tradition nearly forgotten in this country—may have been a contributing factor.

Peter Weibel always viewed the aspirations of the Enlightenment as central to his own intellectual doings as a libertarian spirit who consistently accorded pride of place to knowledge and responsibility. It would follow that criticism and subversion embody prerequisites for the ability to think about freedom at all. His physical presence will most certainly be missed—but his intellectual heritage will, happily, allow us to remain in communion with him.

Günther Holler-Schuster

Günther Holler-Schuster is an art historian, writer, curator, and artist. He works as curator and head of the collection at Neue Galerie Graz, where Peter Weibel served as chief curator from 1992 to 2011. Together with Martin Behr, Holler-Schuster has been part of the artist duo G.R.A.M. since 1987.

March 2023