Július Koller awarded the State Prize by Slovak President Zuzana Čaputová

/4

I would like to reflect here on what establishes not only the artistic, but also the social relevance of the artist’s legacy. How did Koller manage to break free from the glasshouse of the so-called unofficial cultural sphere in the former Czechoslovakia and assert himself in the new conditions of contemporary art after 1989? Answering this question is not at all easy, because it does not suffice to say that Koller’s pieces met the demands of the Western market or that his work corresponded to Western ideas of the “East European Other.” After all, Július Koller was neither a dissident nor an opponent of the communist regime, and his criticism of political and social conditions was so sophisticated that it could not directly threaten the totalitarian regime. To some people nowadays, his systematically elaborated critical position may seem perfectly neutralized, and the subversive power of his works may seem nostalgically outdated.

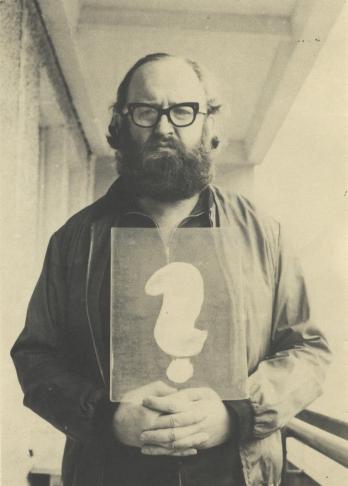

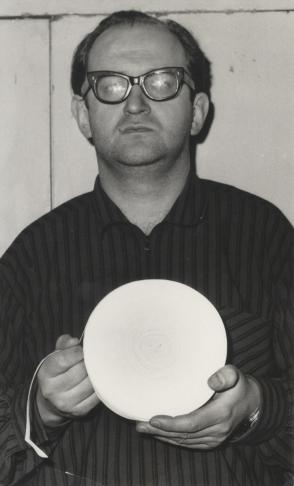

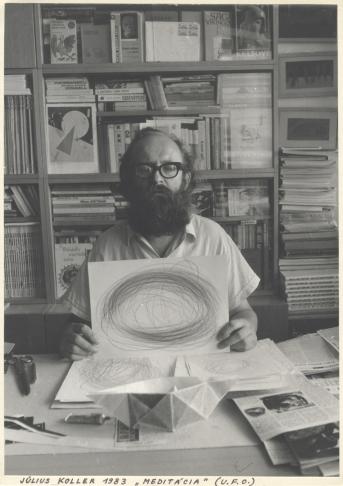

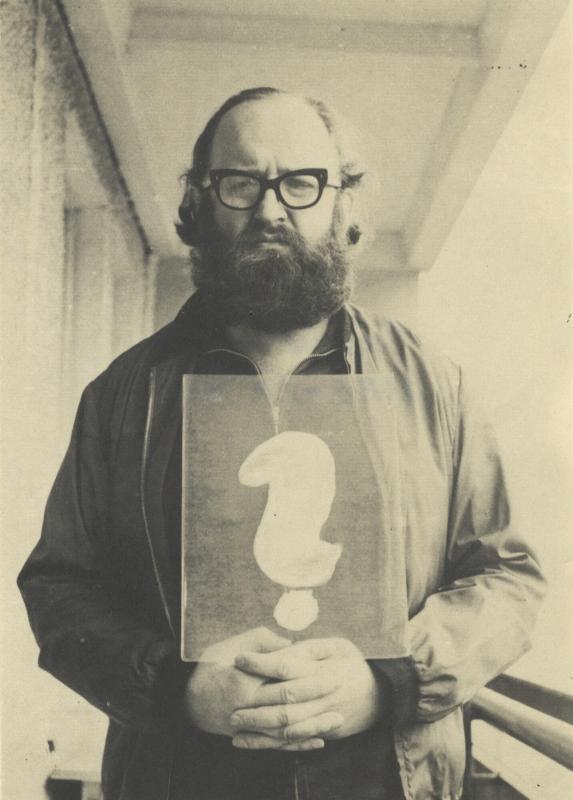

But let us notice how the futurological dimension in his works broke out of the technological optimism of the last century. How the interest in the means of communication was perfectly translated into simple and legible ciphers of transformation in his performances. How through contact, in games, and in the confrontation of banal objects with the human body, the artist stimulates people to think differently, establishing the possibility to rewrite one’s own life, one’s own existence into a communicative medium. How he invites us to follow the proletarially modest permanent provisionality of the culture of life. How he gives us the opportunity to appear and disappear, to enter and exit, to come and go, to use forehand and backhand. How he encourages us to see Umenie / Art = UmeNie / No Art = U.F.O. everywhere. Koller was able to turn these means into artistic signals and use them to activate not only his fellow players, but also to non-violently involve everyone who had only been passively watching before, thus engaging art and non-art circles.

It is precisely the non-violence of participation that lies in the ritual inconspicuousness of transforming the infrastructures of mundane everyday operation into an opportunity to travel to another space-time. Language games have been an integral part of its universe since the beginning. But this universe is not dictated by any theory or ideology, avant-garde or other. It requires no compulsory study of the principles and laws of modern art, no elitist personification of art as the essence of beauty and truth.

A Möbius strip, a spiral, a wave, a question mark, a tennis ball... Everything fits together perfectly in an unbroken continuum.

It is not easy to answer the initial question, but none other than the artist himself can help us achieve that. Koller wrote down in 1971 as a direct reaction to the book “Homo Ludens” by the Dutch culturologist Johan Huizinga: “I am interested in the synthesis (combining, mixing) of ‘play’ and ‘ordinary life’ – the transgression, the making unclear of the boundedness, the closedness, the finality of a play entangled ‘indeterminately’ in life – such ‘my play’ does not end, it goes on and on in an indeterminate rhythm and intensity – it is the ‘culture of life’ – it is not bounded like a playground and a game, neither by time nor space – (but is determined). I would like to make ‘life’ a cultural game with fair and firm rules for everyone...”

Koller contests those who claim that play and ordinary life cannot merge, that they must remain separate, but his position is not voluntaristic. He desires fair and firm rules that are a prerequisite for equal opportunity for all – regardless of race, gender, class, and social affiliation, we might add. Take his many years of public enlightenment activities with amateur artists. He saw the artistic potential in every person and treated all his fellow players as equal partners. He introduced practices that parallel emancipatory and generative pedagogies. Amateurism inspired Koller as a creative principle in working with worthless materials, spontaneous practices of playfulness, and improvisation.

His conceptual work is an endless loop of self-questioning appropriation, at the end of which there is always a new beginning: the cultural situation. The artist is a creator and a signaler, a network designer and an agent of cognitive interconnections between the cosmos, the Earth, and humanity. As an active player in the artistic field, Koller absorbed and critically processed into his work the extensive cultural and social context of the crucial political turning points of the former Czechoslovakia – the years 1968 and 1989.

Just as after 1968 he was not a passive observer, but rather initiated the legendary “J.K. Ping-Pong Club” (1970), so again, in the decisive moments before the fall of the communist regime, he joined important social movements, such as the collective performances of visual artists together with rock, jazz and punk musicians “The Devil’s Wheel” (Čertovo kolo) organized by Ladislav Snopko (1987-88), or the exhibitions Prešparty (1988) and “Basement” (Suterén – 1989), and co-founded the association Gerulata and the art group “New Seriousness” (Nová Vážnosť – with Peter Rónai) and many others. Equally legendary are his performances at several years (1988, 1990, 1992 and 1995) of the international festival of performance art and experimental music “Transart Communication,” organized by Studio Erté in Nové Zámky. It was precisely the Studio Erté (co-founded by Ilona Németh and Jószef Rokko Juhász) that, in the peripheral conditions of minority culture, created temporary zones for integrating all kinds of otherness from all corners of the world.

In the 1990s, when Czechoslovakia dissolved, he worked closely with the curators Jana and Jiří Ševčík, who, together with Czech artists, introduced Koller as a representative of Eastern European postmodernism (“Zweiter Ausgang,” 1993). Koller foresaw the onset of the dark forces of nationalism, and he incorporated them into his paintings fearlessly and with a great deal of humor. Painting as a process, but not an artefact, represents his permanent polemic with professional or so-called high art, artistic academicism, and the overall values dictated by the art market. All these circumstances brought Koller to the threshold of worldwide success, in which his friends living outside his home country played a significant role. Therefore, one can say that the JK’s concept of a planetary cosmohumanist network has ultimately reached its goal. And this network is and will be above all a cultural medium of communication that playfully connects and defends us against manifestations of authoritarianism, violence, rudeness, and narrow-mindedness.

Daniel Grúň, The Július Koller Society, Bratislava

March 2024

https://www.kontakt-collection.org/people/29/julius-koller/objects

But let us notice how the futurological dimension in his works broke out of the technological optimism of the last century. How the interest in the means of communication was perfectly translated into simple and legible ciphers of transformation in his performances. How through contact, in games, and in the confrontation of banal objects with the human body, the artist stimulates people to think differently, establishing the possibility to rewrite one’s own life, one’s own existence into a communicative medium. How he invites us to follow the proletarially modest permanent provisionality of the culture of life. How he gives us the opportunity to appear and disappear, to enter and exit, to come and go, to use forehand and backhand. How he encourages us to see Umenie / Art = UmeNie / No Art = U.F.O. everywhere. Koller was able to turn these means into artistic signals and use them to activate not only his fellow players, but also to non-violently involve everyone who had only been passively watching before, thus engaging art and non-art circles.

It is precisely the non-violence of participation that lies in the ritual inconspicuousness of transforming the infrastructures of mundane everyday operation into an opportunity to travel to another space-time. Language games have been an integral part of its universe since the beginning. But this universe is not dictated by any theory or ideology, avant-garde or other. It requires no compulsory study of the principles and laws of modern art, no elitist personification of art as the essence of beauty and truth.

A Möbius strip, a spiral, a wave, a question mark, a tennis ball... Everything fits together perfectly in an unbroken continuum.

It is not easy to answer the initial question, but none other than the artist himself can help us achieve that. Koller wrote down in 1971 as a direct reaction to the book “Homo Ludens” by the Dutch culturologist Johan Huizinga: “I am interested in the synthesis (combining, mixing) of ‘play’ and ‘ordinary life’ – the transgression, the making unclear of the boundedness, the closedness, the finality of a play entangled ‘indeterminately’ in life – such ‘my play’ does not end, it goes on and on in an indeterminate rhythm and intensity – it is the ‘culture of life’ – it is not bounded like a playground and a game, neither by time nor space – (but is determined). I would like to make ‘life’ a cultural game with fair and firm rules for everyone...”

Koller contests those who claim that play and ordinary life cannot merge, that they must remain separate, but his position is not voluntaristic. He desires fair and firm rules that are a prerequisite for equal opportunity for all – regardless of race, gender, class, and social affiliation, we might add. Take his many years of public enlightenment activities with amateur artists. He saw the artistic potential in every person and treated all his fellow players as equal partners. He introduced practices that parallel emancipatory and generative pedagogies. Amateurism inspired Koller as a creative principle in working with worthless materials, spontaneous practices of playfulness, and improvisation.

His conceptual work is an endless loop of self-questioning appropriation, at the end of which there is always a new beginning: the cultural situation. The artist is a creator and a signaler, a network designer and an agent of cognitive interconnections between the cosmos, the Earth, and humanity. As an active player in the artistic field, Koller absorbed and critically processed into his work the extensive cultural and social context of the crucial political turning points of the former Czechoslovakia – the years 1968 and 1989.

Just as after 1968 he was not a passive observer, but rather initiated the legendary “J.K. Ping-Pong Club” (1970), so again, in the decisive moments before the fall of the communist regime, he joined important social movements, such as the collective performances of visual artists together with rock, jazz and punk musicians “The Devil’s Wheel” (Čertovo kolo) organized by Ladislav Snopko (1987-88), or the exhibitions Prešparty (1988) and “Basement” (Suterén – 1989), and co-founded the association Gerulata and the art group “New Seriousness” (Nová Vážnosť – with Peter Rónai) and many others. Equally legendary are his performances at several years (1988, 1990, 1992 and 1995) of the international festival of performance art and experimental music “Transart Communication,” organized by Studio Erté in Nové Zámky. It was precisely the Studio Erté (co-founded by Ilona Németh and Jószef Rokko Juhász) that, in the peripheral conditions of minority culture, created temporary zones for integrating all kinds of otherness from all corners of the world.

In the 1990s, when Czechoslovakia dissolved, he worked closely with the curators Jana and Jiří Ševčík, who, together with Czech artists, introduced Koller as a representative of Eastern European postmodernism (“Zweiter Ausgang,” 1993). Koller foresaw the onset of the dark forces of nationalism, and he incorporated them into his paintings fearlessly and with a great deal of humor. Painting as a process, but not an artefact, represents his permanent polemic with professional or so-called high art, artistic academicism, and the overall values dictated by the art market. All these circumstances brought Koller to the threshold of worldwide success, in which his friends living outside his home country played a significant role. Therefore, one can say that the JK’s concept of a planetary cosmohumanist network has ultimately reached its goal. And this network is and will be above all a cultural medium of communication that playfully connects and defends us against manifestations of authoritarianism, violence, rudeness, and narrow-mindedness.

Daniel Grúň, The Július Koller Society, Bratislava

March 2024

https://www.kontakt-collection.org/people/29/julius-koller/objects