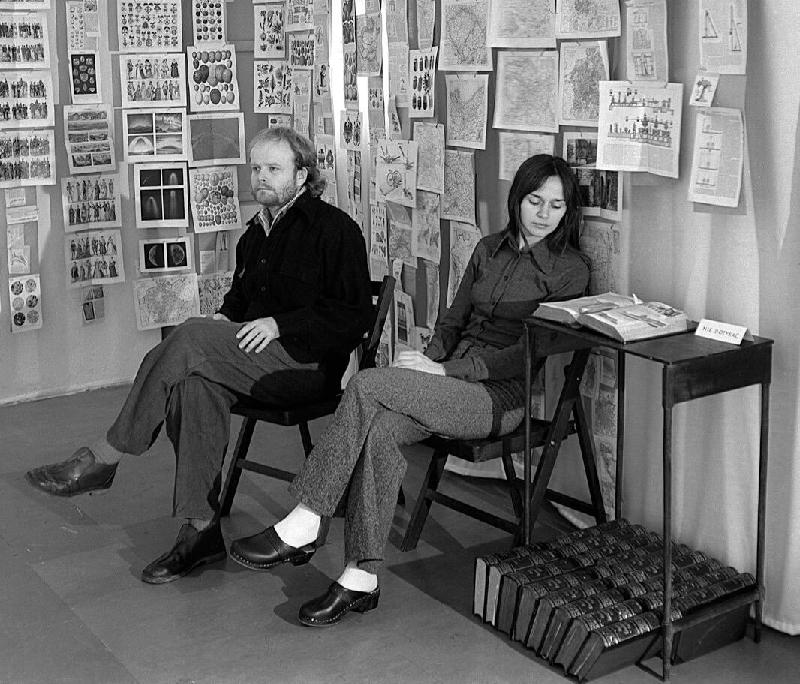

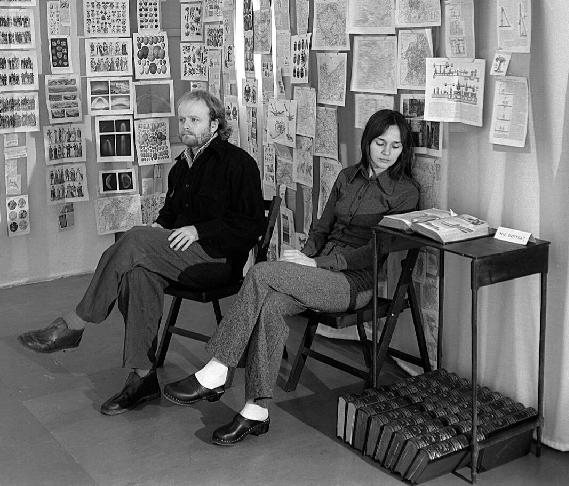

KwieKulik

When Zofia Kulik and Przemyslaw Kwiek started the complex experiment to collaborate as KwieKulik in the beginning of the 1970s—analyzing and reflecting on their everyday life, their private and public existence as a couple, and their creative work with Socialist concepts—their work was accompanied by political considerations and artistic demands for a new role of the artist in society. The forms of representation of these considerations and the questions that they raised related to the status of contemporary art in general and provided the thematic framework for a particular project that developed

for nearly two decades. It is a project that finds few analogies in European art of this period: a couple that used its artistic and private existence as a model for an ongoing aesthetic/political action, as a reformist-motivated, praxeological workshop for the education of an emancipatory society within the framework of state socialism. It was a specific moment in Polish (art) history when Kulik and Kwiek started their artistic partnership and their semiological and analytical reflection on the relationship between societal form and practice that aimed at the rejuvenation of everyday life under socialism, riddled as it was with bureaucratic routine. The Moscow nomenklatura had just put a stop to the cultural warm-up exercises of the modernist Sweet Sixties in the post-Stalinist Soviet Empire. The new conservative rigidity of cultural politics after 1970 intended, among other things, to prevent the ideas of the Prague Spring of reform from living on. While the neo-avant-gardes that formed in the Soviet Bloc were being pushed out of public perception into inner or real emigration, the seemingly liberal political climate and the rhetoric of social reform of the early Gierek years allowed the second generation of the Polish neo-avant-garde, young, pop-spiced late- or post conceptualists an audience and even space for public representation within the institutional framework of the official art system. Envy of Polish liberties spread beyond the Warsaw Pact states. Though these ultimately remained gestures whose symbolic integrationist power was not enough to lastingly secure the legitimacy of the system, they had opened up prospects to reformist possibilities and clearer insight into the insoluble contradiction between the imaginary space of Socialist power and the real space of Socialist everyday life. These new prospects for KwieKulik, when reconsidering the social role of the artist, seemed to be, at the very least, opening possibilities of actuating educational processes aimed at open and emancipatory structures in both artistic practice and its institutional frameworks. Contrary to most of their co-combatants of the second generation of Polish conceptualists who neglected this perspective and addressed themselves to either rigid formalisms, private mythologies, media self-reflection, or a hippie, pop-cultural and alternative cynicism, the couple took the call for reform literally, but with a specific task in mind, namely framing the analysis of regimes of form and discourses on the aesthetic as a social and political project. For KwieKulik, the 1970s’ cultural reforms were regarded as the most distinct symptoms of the absence of something – the social factor. G.S.

more(collaboration from 1971 to 1987)

1947, Wrocław / PL; 1945, Warszawa / PL