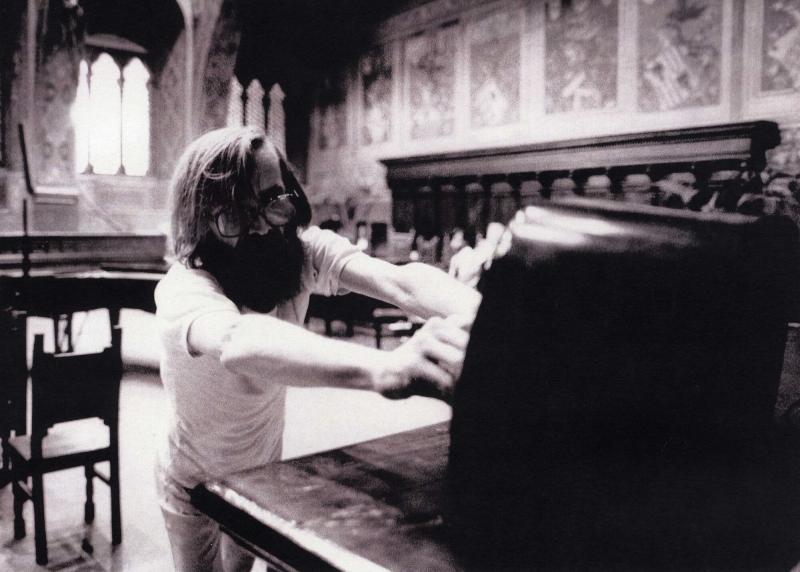

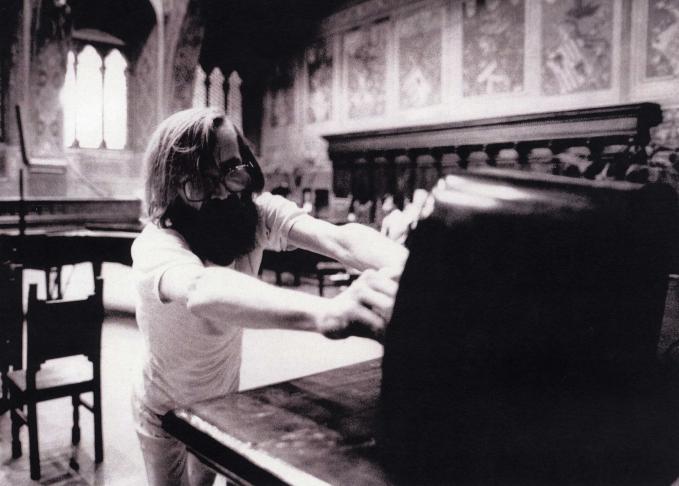

Milan Adamčiak

At the beginning of Milan Adamčiak’s lone self-search was “ignorance, insolence, and a desire for knowledge.” As a conservatory student in Žilina, Slovakia, he willfully prolonged his trip to the Warsaw Autumn festival (1964) where he got to know New Music. In the context of a gradually relaxing atmosphere in art, he followed the line of discovering experimental poetry, happenings, and the Fluxus movement – and he listened to a radio report on John Cage’s visit in Prague. To the young tireless seeker, and an author whose focus was polyhistoric and polymusical —one might say

intermedial—from the very start, this discovery opened a path from which nothing would lead him astray. Adamčiak began creating first abstract drawings intended for acoustic decoding and did not care whether this would happen only in the imagination, in the audience’s minds, or in reality. He did not need traditional performers to confirm the performability of his drawings that are a form of visualizing music. After all, they can certainly be performed if at least one person succeeds in performing them. He carried out various acts of “rebellion” or engaged in action-filled commentaries of everyday situations in a real environment. Adamčiak’s later endeavors include events, instructions, collages, visual poems, phonic/sound poetry, conceptual texts, stamp poems, scores, intentiograms, drawings for acoustic interpretation (graphic scores), acoustic books, and volumes of experimental poetry. With Jozef Revallo, they founded Ensemble Comp. and performed with it for 1. večer Novej hudby (1st Night of New Music, 1969) and Vodná hudba (Water Music, 1970). Working with Robert Cyprich, who was fluent in English and French, and Adamčiak in Russian and German, they started corresponding with artists from around the world, such as Max Bense, Marshall McLuhan, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Dick Higgins, Joseph Beuys and many others. They distributed their works by mail, and by the late 1960s, already became part of a highly active international scene and represented the youngest among Slovak neo-avant-garde artists. They were among the performers at the – considered legendary today – I. Otvorený atelier (1st Open Studio) in Rudolf Sikora’s house in Tehelná Street in Bratislava. In 1969, to demonstrate his attitude at a critical time in his nation’s history, Adamčiak joined the hunger-strike on behalf of Jan Palach, which took place in the entrance hall of Comenius University in Bratislava, where 19 students took part. In the course of the 1970s and 1980s, Adamčiak’s name gradually disappeared from exhibition projects, which was partly caused by the political situation in those times, when hardline Communists dominated Czechoslovakia. In the late 1970s, he formed a close relationship with Július Koller who regularly invited him to meetings of non-professional/amateur artists mentored by him; Adamčiak agreed to join three of Koller’s summer symposia, and he exhibited as an amateur graphic artist. This was at a time when academic artists like him were prevented from exhibiting officially – however, their work could be seen at amateur photography exhibitions, which gave rise to a strong generation of Slovak conceptual photography artists that significantly influenced the history of Czechoslovak photography. M.Mu.

more