Miklós Erdély

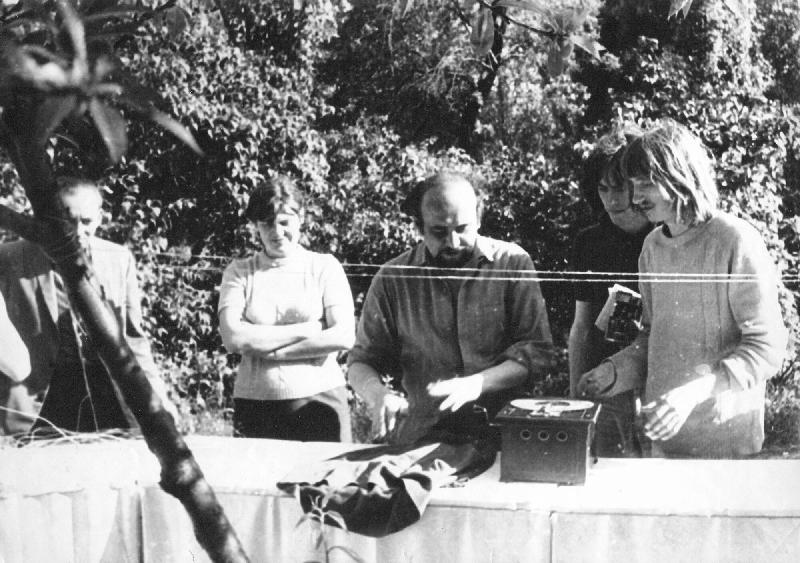

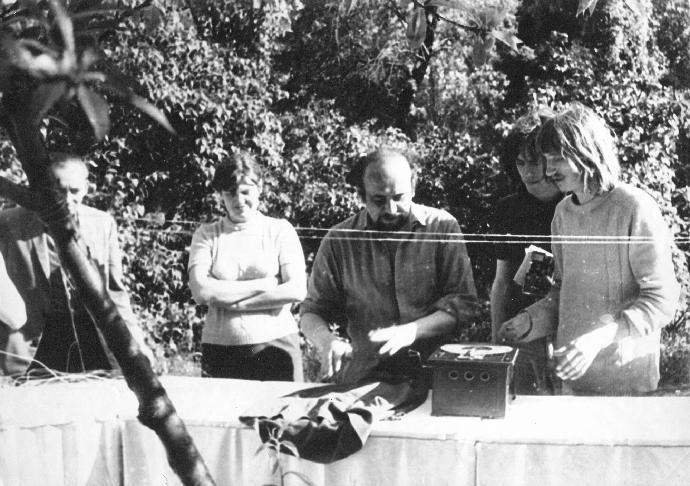

The confrontation and montage of differing theories and mediums characterizes Miklós Erdély’s entire oeuvre. As a young architect in the early nineteen-sixties, he began creating scientifically inspired poetic texts and montage films; later on, he came into contact with the Hungarian neo-avant-garde and Fluxus movements. During the second half of the sixties, he began staging his essentially theoretical and pseudo-scientific texts as performances and “actions” (such as “Three Quarks to King Marke,” 1968). Parallel to this, he produced pop art objects, photo montages, and—later on—arte povera-like

environments with deep philosophical connotations. In these environments (e.g. “In Memory of the Council of Chalcedon,” 1980), he took everyday materials (plate glass, bitumen, tarpaper, matzo, lead) and reinterpreted them in light of various scientific, philosophical, psychological, political and mystical connotations. The seventies, then, saw him develop a specific theory of art that combined avant-garde montage theory with modern scientific theories and paradoxes from the fields of topology, set theory, quantum physics, relativity theory and quark theory. Erdély’s work is decidedly non-object-centered, but it was also not a matter of the “simple” illustration of his own theory, as he considered the process of creation to be the essence of art. Based on this approach, he established a significant alternative art-pedagogical practice in Budapest. It was from this practice and his course (“Creativity Exercises,” 1975–1977) that the activity of the so-called InDiGo group developed, and even just this group’s name represented the melding of theoretical and practical innovation, such as interdisciplinary thinking and the exploration of new mediums such as indigo paper. Parallel to this activity, Erdély dealt intensively with filmmaking, in which he engaged with the language of film while also reflecting on such important issues as totalitarianism (“Spring Execution,” 1984) and racism (“Version,” 1979). During the eighties, alongside creating large scale installations (“Military Secret,” 1984), Erdély also “discovered” and reinterpreted the medium of painting which, unlike the postmodern zeitgeist, served to “illustrate” his art and theory as a kind of visual aid. His earlier graphic art (indigo drawings) and paintings had likewise been attempts to subvert the common sense and “naïve realism” (to quote Max Born) of everyday thinking. S.H.

more